A couple weeks ago, Bang on a Can announced that they were calling off a big project: Long Play, a multi-day festival in Brooklyn in May. It was to be — and hopefully will be, in the future! — a major new initiative for the organization, a kind of NYC-based Big Ears. I wasn’t planning to attend — what with the baby coming in June — but I was very excited to hear about it. I even had a placeholder sentence in my book’s epilogue about it! (Bang is also putting their archives online in early May, which is going to be very exciting! I’ll probably newsletter about that.)

Anyway, coronavirus has done its thing, and there’s no festival this year. But they scrambled to do something meaningful instead, as Bang on a Can always does, and on Sunday at 3pm they’re returning to their perennial marathon format, but all-online, and from-home. It kicks off with Meredith Monk and concludes with Vicky Chow playing John Adams, with around six hours of music in-between. I’m pumped. Here’s the link.

As it turns out, this isn’t the first time that Bang on a Can has had to change its plans last-minute. Story time! Way back in June of 1991, Michael Gordon, David Lang, and Julia Wolfe were all set to present their fifth festival — concerts by Glenn Branca and Arnold Dreyblatt, performances of Harry Partch’s The Wayward, and the marathon — at the R.A.P.P. Arts Center, a multipurpose, dilapidated venue on a rough block on the Lower East Side.

(I got this amazing photo from Michael Gordon; flanking Gordon and Wolfe are the members of PianoDuo.)

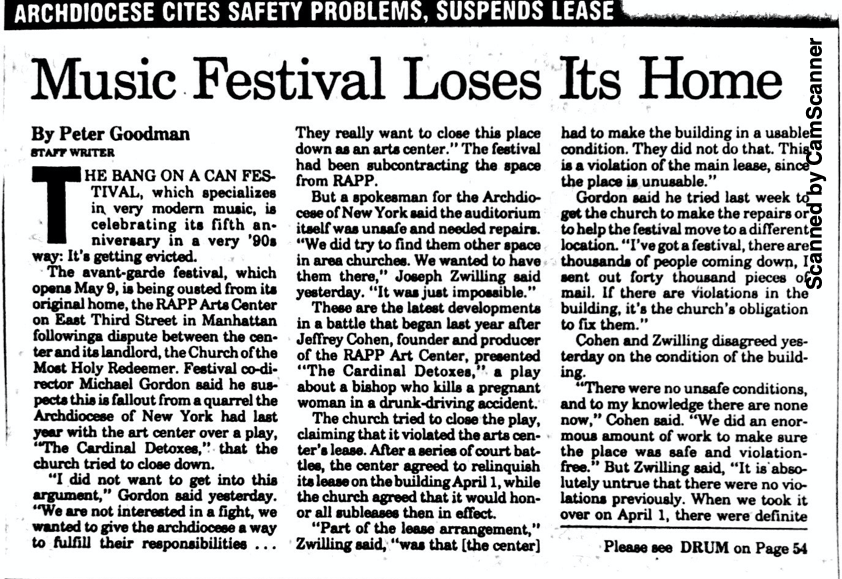

R.A.P.P. had been the festival’s home for a few years, but it also became the site of a significant local controversy in the early ‘90s. The center was owned by the Catholic Church, and the previous fall, R.A.P.P.’s founder and producer, Jeffrey Cohen, had staged “The Cardinal Detoxes”––a play about a real-life bishop who had killed a pregnant woman while driving inebriated. Cohen was courting controversy: the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York attempted to shut down the play and even padlock the theater (very strong “Cradle Will Rock” vibes!!), as Cohen had signed a morality clause in order to rent the space. The church succeeded in evicting R.A.P.P., but had agreed to honor existing contracts with organizations subleasing the venue, including Bang on Can. But as the festival approached, the Archdiocese stated that the center’s auditorium needed repairs and was unfit for use, and they kicked them out.

Here’s some local coverage I found at the NYPL a long while back:

Bang on a Can scrambled, and ended up hosting the concerts at La Mama and Circle in the Square. According to a grant application I found in the NYSCA archives, they lost about twenty grand in the process. Here’s an excerpt from Kyle Gann’s Village Voice review of the festival.

“We are starting again from zero,” Cage said. It seems newly relevant, especially because there’s a broader context to this minor avant-garde vs. Catholic Church tiff, which I have a whole book chapter about, and for which this incident serves as an introductory anecdote. In the Voice, art critic Richard Goldstein mentioned the Archdiocese/R.A.P.P. battle in the context of the obscenity court cases against Robert Mapplethorpe and 2 Live Crew; in this period artists faced hostility from the religious right and Republicans in Congress, a phase of the Culture Wars that began in 1989 with assaults on the NEA from Jesse Helms and culminated in the 1995/96 slashing of the Endowment’s budget by 40% and elimination of support for individual artists. There were significant effects on new music, too. All will be told in the book.

The arts were endangered in the 1990s, and they’re in danger again: the tendency in how we view the past, these days, is to look at how “eerily prescient” or “eerily reminiscent” certain episodes are of our current moment, whatever that may be. But in cases such as these, it’s not just that “this random old thing is newly resonant,” it’s that the past is continuous with, and prologue to, the present. We are living with the world that the 1990s created for us, an era of privatization of public goods that has left us without the social safety net we need to survive a global pandemic. But it’s not just about healthcare: the late twentieth century featured the decimation of a not-nearly-robust-enough public funding system for the arts in the United States. Unlike other peer institutions, Bang on a Can endured through those lean years -- it was their first decade, and they actually grew -- and I now know a lot of reasons why. (The book is almost done.)

I don't have much of significance to contribute to the what-the-arts-will-be-like-when this-all-ends question, if this all ends. Zach Finkelstein is the most astute chronicler of this moment. But I am wondering: who will endure today?

Anyway, I’ll be watching the marathon, excitedly, on Sunday, over at The Road to Sound. Georgia may join as well; she had fun on campus today.